I consider myself to be good at arguing. I don’t mean good at shouting over people or good at debate, I mean pretty specifically that I am good at arguing: when we’re not trying to prove a point, when we’re just scuffling, and I’m trying to get a win by the use of language. When I’m serious, my approach is generally analytical. I’m not invincible but I know what I’m doing. I bring this up because there isn’t a lot of material about this kind of arguing, and because I think this kind of arguing can provide insight into how knowledge and power interact on a mechanistic level.

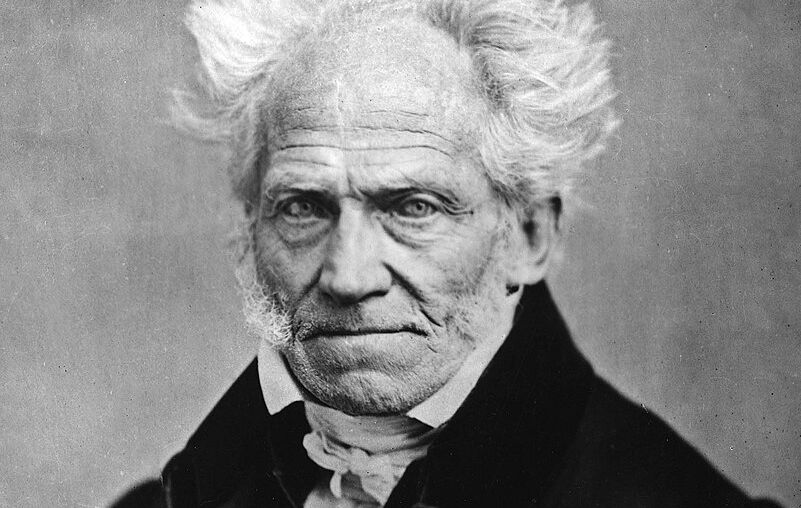

In looking for some ground to mine I’ve come upon the concept of eristics or, broadly, disputation. This seems to have been very little worked on. There is a field called argumentation theory (of which eristics is usually considered a part), but this field is primarily interested in logical argumentation aimed at either elaborating a point or making an inference from known facts. I call eristics a concept rather than a field because there are very few treatments devoted to this type of arguing (aka disputation). I think that I will end up looking at a lot of pop psychology and self-help whenever I get time to look further in, just to find out a broader idea of how our culture thinks about disputation. There is one piece that appears to be seminal, though Wikipedia’s article makes it seem as though the work is a satire. I’m not of this opinion. The book is by Arthur Schopenhauer and it’s called The Art of Being Right.

What Schopenhauer does in this book, primarily, is lay out the various tricks and strategies one can use in a dispute. If you have argued a lot, you will recognize most if not all of these. What’s more valuable to me, however, is what he says about the general field of disputation. He identifies eristics as an endeavor where the object is not to seek truth but to win the dispute. I think, to perhaps split a hair, he is right about the goal, but the motivation of each participant is slightly different: their individual goal is to end the dispute with the greatest amount of power-respect or face (for lack of a better term) possible. From the outset of a dispute each person wants to win but, as the dispute goes on, attempting to win outright may not be the best way to preserve their face.

When in a dispute, people attempt to connect themselves to different concepts, using their influence as part of their struggle against their opponent. Even occurrences like someone getting angry, someone bringing up irrelevant information, someone sticking to a party line, these represent links to different concepts which are interpreted by all sides in the dispute. Each concept has a different value to every different observer, but the values that two people have of the same concept are linked. There is a sense in which having the high hand (as it were) regarding the concept gives one authority over the concept; demonstrating a thorough knowledge of biology, for instance, makes it much less likely that someone with less knowledge will challenge you on that subject. It’s something like capturing an enemy piece in chess or taking a chokepoint in a war simulation. The exact mechanisms that connect people to concepts to other concepts to people and back again are still to be figured out, I think. Schopenhauer’s stratagems will provide a great guide to analyzing those mechanisms.

Eristics has been neglected for a long time, and perhaps it’s right that people were not concerned with it when they thought it was simply about highlighting the ways that crass people manage to overwhelm evidence with bluster. But because eristics is concerned with disputation, with trying to gain and retain power by the application of mental concepts, I think it can provide a window into how power and concepts interplay and how they allow us as persons to interact with one another on an intellectual level.

Leave a Reply